The Economist

Big carmakers

Size is not everything for mass-market carmakers. But it helps

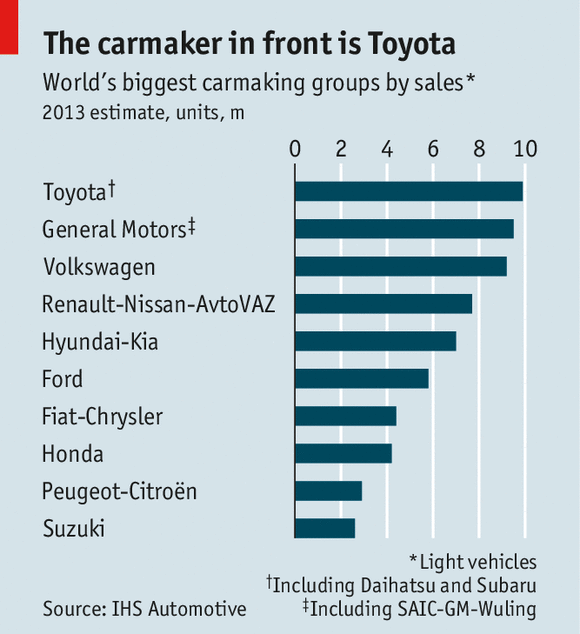

AS THE first estimates of worldwide car sales in 2013 come in, it is clear that Toyota, when its production is combined with that of its affiliates Daihatsu and Subaru, is on the brink of becoming the first member of the “10m club”. It will swiftly be followed by GM and Volkswagen (see chart), both of which are also enjoying continued growth, especially in the world’s largest car market, China. Makers of luxurious models with strong brands, such as BMW and Jaguar Land Rover, can do well selling relatively small volumes of cars for handsome profits. But despite rising sales in America and Britain, and the apparent end of a six-year downturn in continental Europe, life is getting tougher for a squeezed middle, selling mainly mass-market models at margins that are slim at best.

There are plenty of reasons why size matters. Besides the obvious economies of scale and the strong bargaining power with suppliers, being big makes it easier, especially with today’s flexible production lines, to offer an ample product range that can exploit every niche. And the biggest carmaking groups are better able to spread the heavy cost of complying with ever tougher environmental regulation in the largest economies.

Carmakers are having to hedge their bets, at enormous cost, on a range of technologies they hope will help them comply with stricter emissions standards: battery, hybrid and hydrogen fuel-cell powertrains, as well as improved petrol and diesel engines. In an announcement that may in part have been crafted to strike fear into the hearts of smaller rivals, VW said in November that it would invest a whopping €84 billion ($114 billion) over the next five years, with two-thirds going to develop new vehicles and technology.

Size is in itself no guarantee of success, nor are those in carmaking’s middle lane bound to fail. But they are under increasing pressure to find ways to compensate for their lack of scale. The most obvious is to get big by merging. On January 1st Fiat struck a $4.35 billion deal to buy the 41% of Chrysler it did not already own from a health-care trust for retired workers. Even the merged Fiat-Chrysler will produce only 4m cars. Fiat will dip into Chrysler’s cash pile to finance a new range of models in the hope of boosting annual sales to 6m vehicles and to increase the proportion of profitable premium cars it sells from its sporty Alfa Romeo and Maserati ranges. But Fiat will remain weak in car-hungry Asia and could do with another deal to make more inroads there.

Deals of the sort that will fully integrate Fiat and Chrysler are one way of getting bigger but the history of carmakers attempting full mergers is not a happy one. Though several have been mooted recently, such PSA Peugeot-Citroën with GM Europe, they are hard to pull off. DaimlerChrysler and BMW Rover both ended up on the scrapheap. In 2005 GM, fearful of landing itself with a troubled partner, gave Fiat nearly $2 billion to buy its way out of a deal that would have forced it to buy the Italian firm outright. Carmakers are wary of repeating the mistake.

Another way of bulking up is to stop short of a merger but to build a broad alliance. Renault and Nissan this year celebrate 15 years of their partnership (which recently took in AvtoVAZ of Russia). The combination of Nissan’s technology and cash and Renault’s management has kept both firms alive. But although they share some platforms and parts, the two have largely remained separate businesses.

Alliances are typically complicated and can come unstuck when the benefits to both sides become unclear, says Andrew Bergbaum, a consultant at AlixPartners. Examples of this abound. Suzuki and VW fell out even before they got started on a planned alliance to make small cars for emerging markets, and the matter has gone to arbitration. Last month GM sold its 7% stake in Peugeot, bought to cement an alliance to build cars together, as the potential cost savings evaporated. Peugeot is now seeking closer ties with Dongfeng, swapping its technology for a road into China.

A more common way to exploit the advantages of scale without the drawbacks of a full merger or broad alliance is through partnerships to share the costs of specific technology. Developing the platforms that underpin vehicles or new engines allows carmakers to share costs and risks. John Leech of KPMG, a consultant, reckons that the industry has never seen so many partnerships. Medium-sized car firms in particular are looking for ways to plug gaps in their product ranges and technology or to reach new markets. Such technology agreements are a good way of making barely profitable models that carmakers are producing, with reluctance, only to comply with emissions regulations.

Carmakers used almost always to develop their own engines. But as the cost of this has risen, and as the car firms have come to realise how little mass-market customers care about who makes what is under the bonnet, Peugeot has teamed up with both Ford and BMW, and GM Europe with Fiat, to develop engines. In China, all foreign makers have had to find local partners to do the final assembly of cars, as a condition of setting up production in the world’s largest market.

Born of a crisis

The Hyundai-Kia group of South Korea is another maker with prospects of joining the 10m club one day. Between them the two firms first dominated their home market (Kia in partnership with Ford), before Kia came under the wing of Hyundai during the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis. Being part of a conglomerate that includes a big steelmaker has also helped the group continue to gain critical mass. It has overtaken Ford, whose plan seems to be to muddle along in the middle by cutting its number of brands and platforms. Although it is trying to revive the faded Lincoln premium brand, it sells almost all its cars with the “Blue Oval” badge.

Max Warburton of Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm, says that size also comes with risks. Producing vehicles for every region in every segment means manufacturing a vast array of cars that add cost and complexity without necessarily contributing much profit. The mass-market SEAT and Skoda brands bulk up VW’s sales but it makes most of its money from flashy Audis and Porsches.

However, the game that the biggest carmakers are in is to survive for the long term as the stragglers fall by the wayside. Every small SEAT that VW sells at a big discount is a sale denied to a struggling European rival, making it harder for it to stick around to compete.

No comments:

Post a Comment